Dear Fellow SoThinkers,

Toute classification est une théorie déguisée,

et ce n’est pourtant qu’en classant les faits qu’on pourra

se mouvoir dans le dédale sans s’égarer

Poincaré (1909)

Welcome to the course/seminar on Critical Thinking in the School of Thinking program. ‘Critical thinking’ sounds like a very familiar concept to most of us — after all, we all like from time to time to take pride in our critical abilities, in our critical mindset or attitude as students, professionals or academicians. But when pressed to ask the question, “what exactly do you mean by ‘critical thinking’?”, many will find it difficult to define or even merely describe what the concept to them means or implies. Indeed, several different, mutually incompatible, but seemingly valid definitions might come up even for one and the same individual:

- the idea of forming one’s own opinion, by pointing out where one agrees/disagrees with somebody else, on a given subject.

- the idea of exposing fallacies: pointing out factual errors or logical fallacies in arguments (someone else’s or your own) concerning a given subject

- the idea of balancing the pros and contras with respect to a decision on the desirability, the feasibility or the veracity of a (statement on a) given subject-matter

- the idea of the aesthetic appreciation of works of art, mostly music, literature and cinema, in some written or spoken form destined for the public

- a specific philosophical school, associated with contemporary French thought.

The background assumption in entries 2 and 3 (to a lesser extend in 1) is that we have some kind of (implicitly or explicitly) indisputable benchmark at our disposal that allows us to discriminate — to make a ‘judgment’, philosophically speaking — between the true and the false, the right and the wrong, the good and the bad. In the past these benchmarks used to be provided for by religion. In our modern cultural context, they are often based on (classical) logic and (natural) science. Hence the at first glance somewhat contradictory appeal to the authority of ‘experts’ as opposed to the mere level of ‘common (by definition uninformed) opinion’ in many debates, even those of a non-strictly scientific nature. This is considered in much of the present public discourse as the commendable, ‘rational’ attitude towards public decision-making, and also valued as the morally good attitude. It does leave space for the expression of different viewpoints, but only to a limited extend, because the fundamental principles and ‘data’ on the basis of which one argues remain in principle outside of the debate itself and will be common to all speakers. This kind of judgments could ideally be carried out mechanically, by a ‘reasoning machine’ so to speak, once the logical ruleset, basic operations, and required data are clear and put into place. Indeed already the famous philosopher Leibniz conceived of such a machine, and the feverish quest for ever stronger “artificial intelligence” shows that this idea(l) continues to exert a profound influence on the cultural paradigms that govern our present technological civilisation.

When one wishes to call into question this common core, then immediately much more is at stake then a mere difference of opinion: one is shaking the foundations of the ‘paradigm’, the core of the fundamental belief system on which the community as a whole in which the debate takes place rests, or at least, is claimed to rest by the group with culturally speaking hegemonic power. Of course it is difficult to appreciate the value per se of attempts to cast doubt on such seemingly basic evidences, because they can originate from bigotry or from brilliance alike — and it will not be always immediately clear which is which, especially not to those who remain ‘within’ the thought system called into question.

The rational intellectual attitude is epitomised in the adagium formulated by Henri Poincaré, today claimed by the two Brussels Free Universities as their ideological standing ground:

Thinking must never submit itself, neither to a dogma, nor to a party, nor to a passion, nor to an interest, nor to a preconceived idea, nor to anything whatsoever, except to the facts themselves, because for it to submit to anything else would be the end of its existence. (Henri Poincaré, 1909)

The problem is of course that also scientific ‘facts’ cannot always so easily be taken for granted. Poincaré stresses precisely this point already in his 1909 address: “Facts are subject to a number of interpretations, because they are never more than only partially known. Among this multitude, there are interpretations which are more likely than others, but sadly enough likelihood is an extremely fugitive, subjective and delicate thing, on which even the finest minds will not always agree.”

So, even when taking all the accessible facts into account, there still remains room for interpretative variance. Thus, Poincaré did not mean that “in the end the facts are the facts, so just shut up”, quite the contrary. No, his stunning claim is that, even if all the facts to the matter are perfectly clear and accessible to all, still irreducibly different but equally valid ‘theories’ (models, in the scientific sense) remain possible. The reason is, basically, that we are always part of the world we want to describe, hence we speak about it from a perspective from within. This, of course, is by no means to say that “the world” is “not real”, or “merely a mental construct”. Nonsense exists — it are the “theories” that doe not take the available data into account when formulating their worldview. It does mean, however, that there are always more than one valid perspectives on the real. Poincaré nicely illustrates this by the story of Sphereland, where the inhabitants of the sphereworld will use another geometry to describe their reality then we, as external observers would (see the references below). But as we all know, taking an external God-like perspective on the universe as a whole is impossible for anything in it as a matter of principle. It is therefore not possible to simply assume that the structures of our (logical) thought, when correct, correspond a priori to the structures of reality, because the way our thought is structured informs the way we perceive the world. One does not have to accept Kant’s original (erroneous) position, that the structures of (Euclidean) space-time are a universal feature of our basic mental set up, to share his fundamental insight that our mental structures are co-constitutive to the structures of our world.

This allows us to come back to the other connotations linked to the concept of ‘critical thinking’ mentioned before, one in which the notion of ‘judgment’ as an irreducibly human activity is taken much more serious. This was already Kant’s concern while formulating his three fundamental Critiques — of pure reason, of applied reason, and of judgement. Critical thinking always implies a perspective, a — literally — stand-point from which the speaker looks upon the subject matter at hand. This ‘Linguistic Turn’ lies at the bottom of so-called the ‘Critical Thinking’ school within philosophy, in which the (awkwardly so called) “Continental School” of contemporary French and German Thought plays a key role. Although not directly our concern here, I want to point out to you that these philosophies are addressing serious problems directly related to what was said above, and not just some heap of incomprehensible gibberish.

Poincaré developed his position into an epistemological approach to exact science which is called, unhappily, “conventionalism”. Conventionalism is not relativism —, it does not claim that “everything is equally true”. It, on the contrary, is a form of realism; a realism that takes an irreducible pluriformity of perspectives on the world into account:

Conventions, yes; arbitrary, no – they would be so if we lost sight of the experiments which led the founders of the science to adopt them, and which, imperfect as they were, were sufficient to justify their adoption. (Poincaré 1902)

So ‘facts’ are never just ‘brute’, they always require human intervention. This epistemological state of affairs has given rise to n even more general hypothesis on the nature of scientific understanding, the Duhem-Quine Thesis:

The Duhem–Quine thesis argues that no scientific hypothesis is by itself capable of making predictions. Instead, deriving predictions from the hypothesis typically requires background assumptions that several other hypotheses are correct; for example, that an experiment works as predicted or that previous scientific theory is sufficiently accurate. (Wikipedia)

As far as experimental, science is concerned, the impact of the choices and actions of the observer/experimentator on the result of his/her observation has been established by now beyond a shadow of doubt by the science that studies the ultimate building blocks of our reality — only to discover that there are no ‘blocks’: quantum mechanics.

Many of you will be familiar with the so-called “wave-partical-duality”, a kind of intermediate, undetermined state, the superposition state, in which elementary particles like photons can find themselves when unobserved. The choices made by the experimentator — e.g., what kind of apparatus he will use, the way the dials are set, etc. — will determine in which of the two mutually exclusive ways a photon will manifest itself: as a (local) particle or as a (non-local) wave. Before its observation, the particle is not in either of them, but in a kind of weird ontological in-between, which contains the two ‘classical’ states as reduced extremes. so what you see as an experimentator is (obviously) real, but it would not have been there without you interfering. Luckily enough, the theory does predict, and accurately, the statistical distribution of the outcomes involved, but never the specific outcome of one measurement. Moreover, potential interactions between the phenomenon observed and parts of the measuring device itself come in to further complicate the picture. Original attempts to explain this away on statistical grounds are abandoned by now, since it has been demonstrated experimentally that superposition and entanglement play their rôle also when a single self-interacting particle is involved, sometimes over hundreds of kilometres of distance. The interpretative problem that goes with this state of affairs is currently known as “The Measurement Problem in Quantum Mechanics” (see the exercises below).

Similar questions arise with respect to other sciences, some quite sensitive with respect to society. In economical predictions the set up of the models and the choice of the factors to be reckoned with determine to a large extend the nature of the predictions they will produce. Relevant examples are transnational Free Trade deals and the models used in climate science (see exercises below).

Beware that the fact that models do deliver different outcomes does not necessarily imply that one model should be right and the other simply wrong.

Some Exercises

a. Perspectivism

Build critical awareness of your own observational perspective.

– Watch yourself. Describe in detail what you can see of yourself. Try to take a look at yourself from different perspectives (sideways, above, below…). Make for each perspective a detailed description, so that it is possible to compare the different viewpoints on yourself that you can take.

– Watch yourself in the mirror (if possible completely). Repeat the exercise.

– Watch someone else. Repeat the exercise. Really take different stand-points and describe the person in detail.

– Compare the three cases and formulate some conclusions. Are there differences in watching yourself form watching some-body else? If so, try to explain precisely what they are.

********

b. The Measurement Problem

– Watch this video. It is not important whether you ‘agree’ with the point of view it takes or not. The point is to try to extract for yourself as much as possible information about the Measurement Problem. Try to summarise for yourself (on the basis of the explanations given, or on the basis of some of the the numerous references) what this whole problem is actually about. Write a few clues down as an ‘aide-mémoire’.

– Read this article about recent discoveries demonstrating observer influence on experiments in quantum mechanics once and for all.

Write down in a few phrases your thoughts and ideas in reaction to it.

********

c. Perspectivism and measurement in QM: a Toy Model

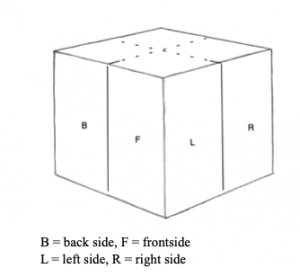

Let us look at a toy model of a firefly in a box to illustrate the simplest possible QM-situation: the superposition states for an isolated, single particle moving in a box. Our ‘particle’ is a firefly that can turn its light ‘on’ and ‘off’ while it moves freely around within. Our experimental set up is a box consisting of translucent windows (so that you can see the moving light, but not the detailed forms of the firefly inside).

You are standing either in front of the box (to the right of the drawing), or to the side, and you can follow the firefly’s motion by following the moving light in the box. The light can be on and off; if it is off, you have no information on the fly’s position whatsoever — it literally can be everywhere.

You share a common world with the fly because your feet are glued the ground on which the box stands; you can glide over it and hence turn around the box, but you cannot lift off. Also, you can look only from one side (perspective) at a time.

– Write down the set of all possible experimental results for this set up when you watch from the front, and when you watch from the side. What can you really know about the position of the fly in the box based on your observations? What is the total set of experimental results? Are there ‘gaps’ in the knowledge about the fly’s position?

Example: watching from the front: {R,L,n}: the fly is Left, Right, or not (invisible)

– What happens when you stand at the corner and watch?

– What happens if you are allowed to add a new perspectival dimension, and take the viewpoint from above, watching down (and detaching yourself from the ‘world’ to which you yourself and the box belong)?

********

d. Perspectivism and modelisation in the economical sciences: a case study

This paper discusses and critically compares models for the economic impact of Brexit:

– Read the introduction, pp. 1-11

– Choose one topic out of the remainder of the text and look into the chapter with the different models that deal with it: what do they predict, what are the main differences? Where do they concur? What factors might be responsible for the differences?

– Make a short note that can serve as a basis for classical discussion.

Beware that the idea is not to develop and present a stance in favour of or against Brexit (you may, of course, but just for yourself), but to effectuate a critical reading of the results presented by the different studies analysed in the text.

********

e. Perspectivism and modelisation in the social sciences: gender studies

This exercise spreads over several days.

Day 1: Write down on a piece of paper spontaneously your answer to the question whether the differences between men and women are primarily biological rather than cultural or vice-versa— a socially relevant instance of the Nature/Culture debate, because it influences the gender-equality debate in society at large. Explain your point of view summarily in not more than a page. Leave it untouched on your desk for one day.

Day 2: Get back to work and look earnestly for five serious counterarguments against your own position in the very rich literature on the subject you’ll find on the internet or in any library at your disposal. Try to forget it is you who took the original position, and concentrate on finding as strong as possible counterarguments from different disciplines (neurology, biology, sociology, history, gender studies, archeology, economy…). Summarise each systematically in a short paragraph (5-10 lines max).

Day 3: Check whether your effort at undermining your own position has changed anything with respect to your original view. If not, did you get anything else out of the exercise?

Some names on the “nature” side: Camille Paglia, Jordan Peterson, John Gray

Some names on the “culture” side: Cordelia fine, Mary Beard, Lise Eliot

********

The assignment

Dear Student,

Upon request a few clarifications on the exercises:

– You don’t have to do all the exercises in your response letter to me. But I encourage you to do them all for yourself (or as many as possible) in preparation of the seminar, since we will use the results in our work and discussions.

For your report I expect the following:

1. Everybody makes the first exercise, titled ‘perspectivism’, on watching yourself and somebody else from different sides. Keep your report short, work with bullet points if you like.

2. You may chose one out of the two exercises relating to Quantum Mechanics, so either

b) The Measurement Problem;

or

c) the Toy Model of the Firefly.

In case you chose b: watch the video or read the paper (or both) and write down in a few paragraphs a short reaction/reflection to what you learned. I do NOT expect an ‘expert level’ reaction at all. Anything you get out of it will do!

In case you chose c: Keep it simple! You DO NOT have to interpret the Firefly from the point of view of Quantum Mechanics, that’s what we will do during class! Just describe precisely what you can observe about the moving Firefly’s position when you’re lokking from the front to the box (and you see the division L/R), when you’re looking from the side (and you can distinguish F/B), or when you’re taking the ‘forbidden’ position from the top.

3. You may chose one out of the two exercises on Human Sciences, so either

d) Perspectivism and modelisation in the economical sciences

or

e) Perspectivism and modelisation in the social sciences: gender studies.

Your report does not need to be very elaborated, again a few paragraphs will do — we shall discuss details in class.

Summarise your work and send me a a short email reporting on how it went. I’m looking forward to hearing from you about this by Tuesday, Oct. 22nd. My email address is: kverelst@vub.ac.be.

Good luck!

Karin Verelst

Supplementary reading material:

See the ‘Alpha-SoT-VUB – Reading assignments – 24-25.10.2019‘ file.